Developing good local projects is the key to the practicum semester (and the whole E-Corps concept). To date, we've had about 50% of classroom students go on to the practicum, so a typical practicum class size may be 10-15 students. This translates to between 3 and 7 projects (more or less). Thus, recruitment of, and communication with, town partners are critical elements to success.

Choosing Projects

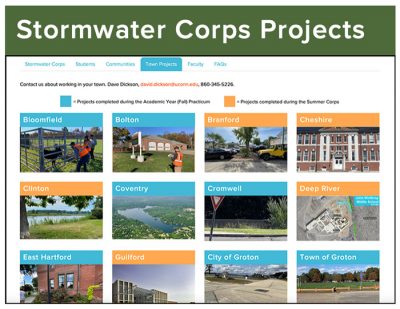

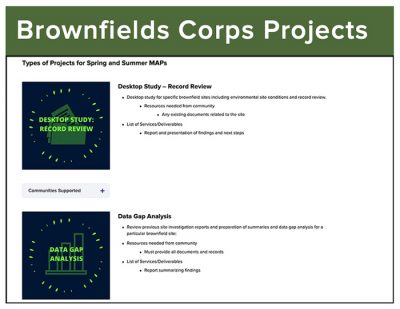

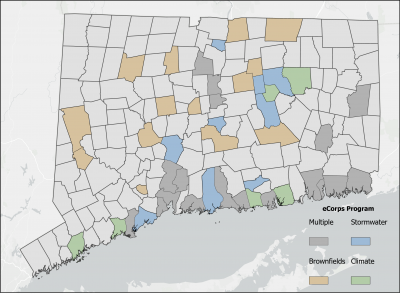

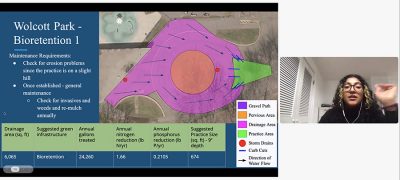

Projects need to be doable for a team of students within the time constraints of a busy semester, and result in a product that is truly useful for the town/partner. As noted in the E-Corps project decision tree, courses that intersect in some way with an ongoing need or opportunity for your communities, such as a regulatory requirement (Stormwater Corps) or grant program (Brownfields Corps), will make your life easier but are not required. Below are the project pages of the three courses, to give you a feel for what the student projects are like. Click on the image to learn more.

Town Partner Recruitment

As noted in Key Elements, partner (client) recruitment for all three E-Corps courses has relied heavily on long-term relationships with communities developed by faculty in the course of their Extension or Extension-like activities. That said, the courses recruit in slightly different fashions and with varying degrees of formal process.

Stormwater recruits through the “MS4” Stormwater General Permit listserv, which goes out to town planners and engineers throughout the state. Click here to see an example.

Brownfields issues a Request for Proposals (RFP) three times per year. Click here for an example.

Communication and Reporting Out

The instructor taking the lead on the practicum semester typically serves as liaison between the town and the student teams, often with help from a grad assistant. Student teams usually have a meeting with town staff before the project begins, to make sure there is agreement on the focus and scope of the project, and for the students to ask questions of, and solicit advice from, town staff. Town staff can also be involved in field work, to varying degrees. Finally, there is the “reporting out” of the results by the students to the town. This critical piece is actually been enhanced somewhat by the use of virtual meetings, which allow more flexibility. The degree to which the instructors facilitate these interactions vary, but much of the responsibility is placed on the students.

Project Logistics and Oversight

Coordinating the schedules of the individual members of each student team can be challenging, especially when it comes to finding sizeable chunks of time for field visits. As noted in Communication, much of the burden of this organization is put on the students themselves; still, it does create somewhat of a ceiling on the size of a workable project team. Also, the farther away a project is, the longer the time set aside for a field visit will take. This has resulted in a slight bias toward working in communities closer to campus.

Actual review and oversight of the projects by instructors varies. Typically, most student projects need comment and a revision or two before they are ready to be presented to the town. This needs to be considered in the timeline/syllabus of the practicum semester.

Workforce Development

The practicum projects present the students with the opportunity to apply in the "real world" the STEM knowledge gained in class. In addition, being team projects (for the most part), the practicum semester requires extensive use of "soft skills" like working in a team, communication with the client, and presenting results. The communication aspects of the practicum project are more than logistics – they provide valuable experience in organizing and real world efforts. In addition, our experience is that the positive feedback that the students receive directly from their community “clients” is immensely gratifying, and in many cases revelatory in that they see that their work actually may make a difference.

We have found through informal feedback that students often use their practicum projects as a talking point during job interviews, and as a particular focal point on their resumés.